Case Study: Laying a Foundation of Continuous Improvement Allows for Rapid Response

WHEELS, a NYC Outward Bound School in Washington Heights, Manhattan

By: Aurora Kushner, Director of Continuous Improvement, NYC Outward Bound Schools

At the start of the 2019-2020 school year, WHEELS had committed itself to engaging in continuous improvement short cycles from preK-12. Continuous improvement — the process of problem and solution identification, and then short rapid testing of those solutions in order to assess the effectiveness of the ideas — is how schools in the NYC Outward Bound Schools network are beginning to move toward more equitable outcomes.

WHEELS, a district public school in uptown Manhattan, had dabbled in inquiry cycles in the past, with mixed results and ownership at the grade team level. But this school year, there were robust plans in place for teacher teams to move towards ambitious student impact outcomes focused on literacy and numeracy goals through learning together, trying new ideas, and reflecting on what their students were able to accomplish. Aligning their work, grade teams monitored student growth and the Instructional Leadership Team (ILT) monitored staff growth. Further, ILT met regularly to compare staff and student growth, and consider what further needs staff had and how weekly professional development would serve those needs.

For example, the 6-8 grades’ goal was to improve the quality of writing through increased sentence fluency. While teachers implemented various sentence- and paragraph-level strategies, such as using transition words in sentences and possible outlines for paragraphs, they also regularly tracked growth in students’ sentence fluency through Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) inquiry cycles.

Eighth grade team leader Rachel Folger commented that, “When we began the inquiry process at the team level, teachers felt like it was just another data point that had to be entered each week. It was viewed more as compliance than learning because of how inquiry had been inconsistent in previous years. However, after a few weeks of looking at student work in team meetings, teachers on our team began seeing student growth and the impact of collective teacher actions. Instead of just looking at numbers, we had deep conversations about students writing and we analyzed each other’s tasks and lessons to see if the strategy we were implementing was impacting student learning.”

As Folger reflected, the 8th grade team “had some challenges in following through on the process,” but built a culture of trust by sharing student work and embracing vulnerabilities as they shared their own work. Over the course of the year, teachers saw the positive impact of their weekly discussions about student work and the small ‘tweaks’ they made to their practice. Folger shared that, “team meetings had a positive vibe because we were focused on student improvement instead of complaining about student behaviors or poor performance. Teachers also started to say that our weekly professional development meetings were more productive. We analyzed each other’s tasks and truly supported each other in a ‘no blame, no excuses’ kind of culture.”

The data compiled from the 8th grade students — while imperfect and reflective of the team’s learning curve — does show an upward trend of student achievement. In looking at their team’s impact, Folger shared, “By the start of our fourth cycle, we started to take a deep look at our students who had plateaued on the rubric, kids who often skate by in the middle. Because of our inquiry process, we were able to identify next steps for these students and target our instruction in every subject area. Our team’s instructional practices were more aligned than ever before” by standardizing practices and seeing results.

Instead of just looking at numbers, we had deep conversations about students writing and we analyzed each other’s tasks and lessons to see if the strategy we were implementing was impacting student learning.

Of course, all of this changed when COVID-19 hit. When NYC schools shut their doors on March 16, grade teams had just wrapped up their fourth inquiry cycle and hit their stride in analyzing student data, deepening instructional practices and learning from their collective work. While the first few weeks of remote learning were devoted to setting up systems, reaching out to students and adjusting to a virtual world, the foundation of team learning was solid, allowing grade teams to pivot their inquiry cycles.

In mid-April, when teams began shifting back into inquiry, the goals changed — not because literacy wasn’t still important — but because the pandemic and rapid shift to remote learning caused a drop in engagement. The new goal became increasing students’ feeling of belonging and membership in the school community, along with increasing engagement in their classes. Teacher teams developed five possible actions to try in order to impact the goal.

A. Teachers increase clarity with narrow long-term targets, criteria and opportunities for reflection.

B. Teachers increase relevance with authentic, real-world purpose for summative task, ideally in local community.

C. Teachers increase access and rigor with options for students to complete tasks.

D. Teachers increase access and rigor with help resources for students to complete and extend.

E. Teachers increase CARR (Clarity, Access, Rigor and Relevance) with meaningful opportunities for students to discuss and engage with each other.

Teams relied on the structures, processes and trust that was built over the year in order to engage in a new line of inquiry, all while balancing learning how to teach in a remote environment. Ryan Berry, 5th grade team leader, reflected on how his team re-envisioned their office hours to better serve the needs reflected in student data. The team engaged in a weekly audit of their synchronous and asynchronous lessons in Google Classroom expecting that strategic and intentional use of learning targets, checks for understanding, authentic use of data and tight models, critique protocols and feedback cycles would increase student engagement. This would be measured by regular attendance at office hours and quality work completion.

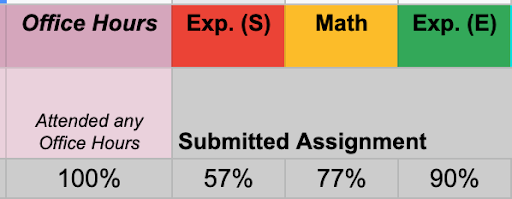

The team’s baseline data showed that only 67% of students were attending any office hours, but by implementing the various changes listed above, they saw their engagement data and submission rates increase.

Week of 5/18 – Prior to implementing change

Week of 5/25 – Week 1 of change

Week of 6/1 – Week 2 of change

Week of 6/8 – Week 3 of change

*Exp. (S) = Expedition Block, Spanish; Exp. (E) = Expedition Block, English

Berry reflected, “It wasn’t perfect, but it was meaningful and energizing work in a time when there was little energy, and meaning was hard to come by.”

While the student impact data does not show major gains in the literacy goal for the year, teacher teams did make progress. And more importantly, regardless of academic outcomes, teacher teams continued learning together about what worked and what impacted student outcomes, all in the face of such rapid and dramatic change. The constant reflection, calibrating over best practices, and learning from failures helped build the “collective efficacy” of teacher teams. Collective efficacy is defined as a team’s shared belief that their shared work can have an impact on students and is at the top of the list of factors that influence student achievement. By adopting the mindsets and practices of continuous improvement, teacher teams at WHEELS built a sense of collective efficacy that allowed them to shift quickly and nimbly to changing dynamics.

Over time, Principal Tom Rochowicz predicts that this will allow his teams to realize the goals they have for their students, sharing, “We frequently talk about how to support students in being ‘leaders of their own learning,’ but our adult learning opportunities also need to reach for that higher bar. Teams of teachers should also be ‘leaders of their own learning’, and inquiry cycles really push them to more deeply consider a student area for growth, a change idea and a way to measure their impact. This ‘cause-effect’ thinking makes clear the impact they can have on student achievement.”

Generalizable Lessons

- Building the capacity of teacher teams to think like a team of researchers, versus as a team of technicians, leads to teachers being able to be leaders of their own learning. When teachers remain in technician mode, they are more likely to go through the motions and to get the work done, but not focus on the improvements needed in the teacher work to have impact on student outcomes. A balance of the two builds in the mindset work needed in order to make improvements over time.

- While there was no clear path forward to engage students in remote learning, since it hadn’t been done before, teacher teams relied on the trust they had built over time to try new ideas. This trust needs to be built over time, and through engaging in work together.

- Having a leadership team composed of administrative and teacher leaders drives staff and student learning when that team engages in its own inquiry process to consider whether teachers are growing in order to have impact on students. Building the capacity of the leadership team further drives teacher learning, engagement and ownership of the growth of our students.